Religion Of Science

Galerie Perrotin, Hong Kong

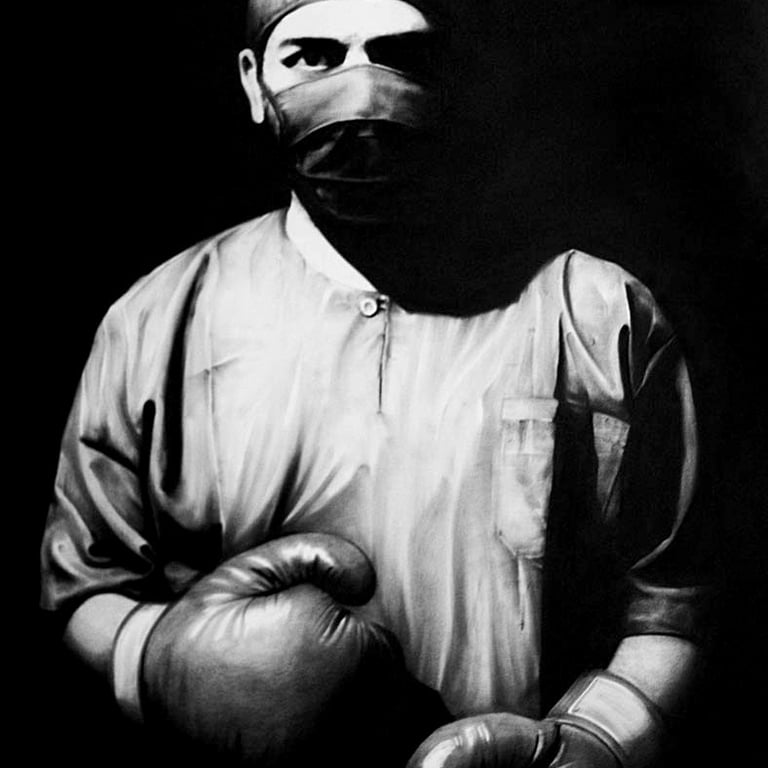

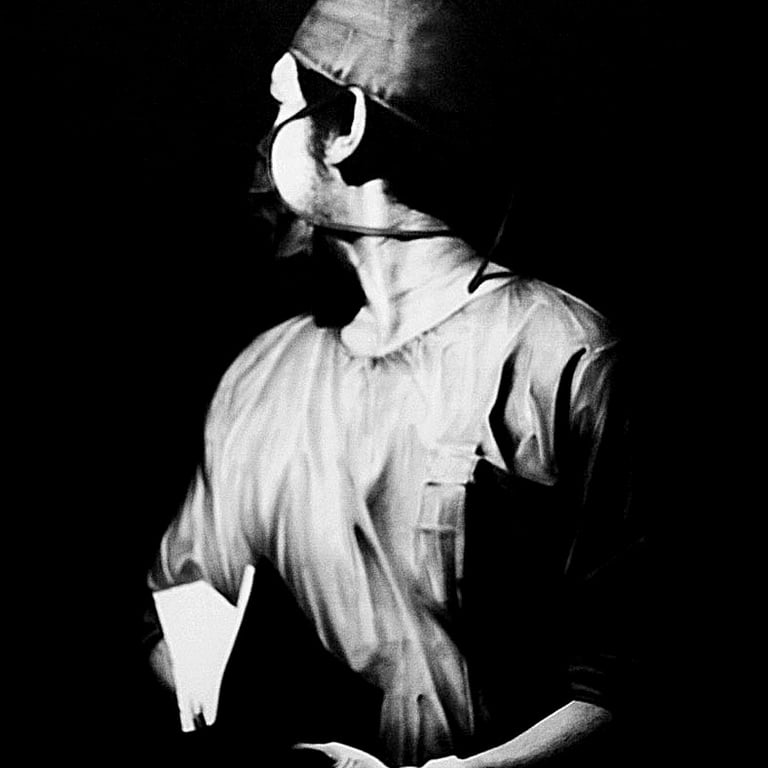

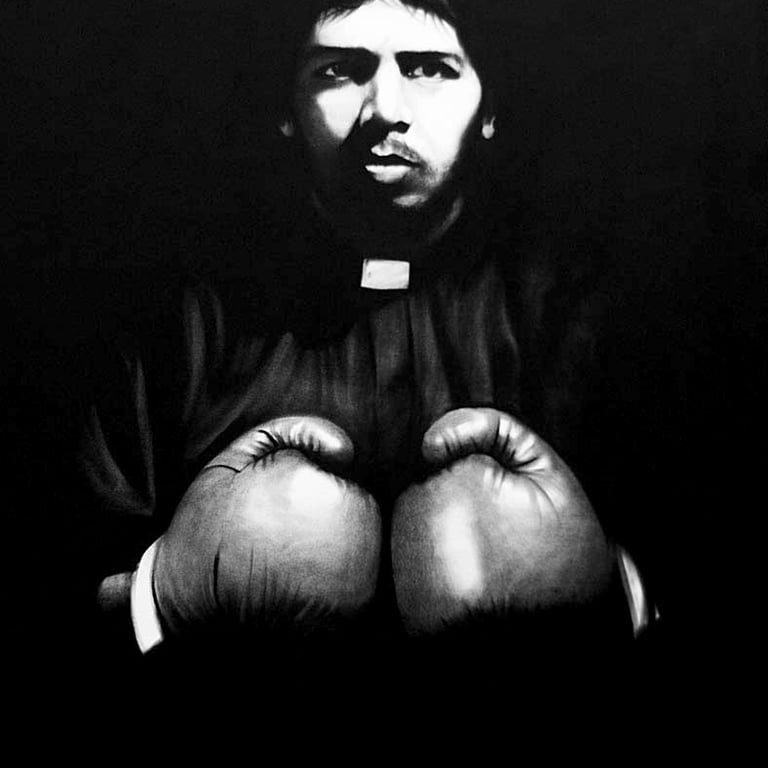

Remarkable for his realistic black and white charcoal paintings, J. Ariadhitya Pramuhendra (b. 1984 in Semarang, Indonesia) creates uncanny realistic portraits and theatrical figurative scenes that evoke Christian iconography, surreal science, and the empowering of self. His works question the spiritual validity of authoritative organisational structures such as organised religions and the medical corps in their search for truth and the divine in man. Pramuhendra investigates the question of one’s core identity, expanding from his own traditional catholic upbringing within the context of practicing Christianity in a Muslim country – the largest Muslim country in the world in fact – visually expressing his search through monochrome aesthetics that draw from figural representation, personal and cultural symbolism, tradition, renaissance, and pop art – in opposition to Islamic religious art aniconism.

When Pramuhendra started showing his religious subject in 2006 he was one of the rare to explore the topic, with the consequence of surprising and raising concerns for his choices among his audience. The artist felt strongly about exploring a way to assert who he was, all the while in the process of discovering it and asking the question to himself. His works are about fully assuming a set of beliefs he just started to explore critically.

Departing from the idea that if an artist is to ambitiously tackle core life questions and universal human issues, then he should start from the study of self, Pramuhendra develops series that stage his representation repetitively, as well as his family’s, in various black and white renditions where he is endorsing the role of Jesus Christ, the pope, a minister, a doctor, in a realistic photographic style yet close to a twenty-first century Georges de La Tour or Caravaggio with chiaroscuro renderings and dramatic potency.

By working on self-portraits, Pramuhendra’s practice echoes the long artistic tradition of self-portraiture. Often showing himself in a position of authority, he points at the power of the robe, and appropriates to himself its strengths and weaknesses. By picturing his spirituality through the one religion he is intimate with and immersed in since birth, his ways echo the ambiguous relationships experienced by some contemporary artists such as Gerhard Richter with the Western Church. But by posing himself and his family successively as the Redeemer, a Catholic pope or a nun; and by visually integrating medical imagery, secular postures and profane body languages, Pramuhendra points at the opposition in concepts between criticising and belonging, practicing blindly and consciously approving, trusting religious leadership and finding one’s own answers through a personal connection with the divine. Somehow managing to mix dramatic effect and a touch of humour by gently creating visual oppositions, Pramuhendra raises universal questions: where is sacred within us, is it in our bodies? Does it belong to the religious leaders? Science? Where does the power of God resides?